Showing posts with label San Francisco. Show all posts

Showing posts with label San Francisco. Show all posts

Sunday, May 17, 2015

Waltzing With Birdie

Uncle Doug was a bachelor. He wore thick, black-rimmed glasses that greatly magnified his watery blue eyes. At 35, he was short, bald and chubby. After World War II was over and his typing stint at Fort Benning, Ga., ended, Uncle Doug came back home to San Francisco. A year later, he and my grandmother used the GI bill to buy a bungalow way up on the hill in Noe Valley. The three-bedroom house, with a tunnel entrance seemed like it was built on stilts, a promontory to the only world I knew – the Mission district down below, the neon Dutch Boy paint sign waving mechanically in the Potrero Districts, and ships, like tiny logs, anchored in the bay beyond.

My mother and father moved the four of us kids into the house’s cavernous basement when my father’s drinking led to the bank’s foreclosure on our tract house in Pacifica. Upstairs, Uncle Doug, Great Aunt Eva and my grandmother slept in the three small bedrooms, huddled together at the end of the long hall. Sunshine flooded in through three big skylights, which eased the despair.

Uncle Doug collected girlie pictures and pasted them into loose-leaf binders like recipes in a homemade cookbook. He kept them on his bureau with all the stats – bust measurements, age, height, weight, other magazines they’d appeared in. Before going to work in the afternoon, Uncle Doug would pace the floor of his bedroom listening to baseball games, calling the plays out loud before they were made. He had a record player and sometimes sang along with Frank Sinatra when the Giants weren’t at bat.

My grandmother said Uncle Doug had “shell shock” from his experience in the war. That was what made him so odd, she said. That was what made him talk to himself and pace like a big cat. My mother rolled her eyes and held her tongue whenever the shell-shock theory was presented. She leaned toward the brain-damaged-at-birth notion.

Sometimes Uncle Doug would go to the basement. There was an old, black upright piano in the back corner, shoved against the cement foundation wall. Our beds were arranged there too. He’d beat the keys, pound out hymns and sing in his thin tenor voice about the love of Christ. My mother would usually take us kids down the street to the park until the music died.

Uncle Doug loved to dance. He went folk dancing on his days off. He’d wear a plaid shirt and tie with a frayed tweed sport jacket. He had high blood pressure and anemia, which he tried to cure by eating raw liver. He picked the ear wax from his ears with a bobby pin and ate it. He smelled like the inside of an old shipping trunk. He never missed a day sorting mail. He turned over his paycheck to my grandmother without discussion.

Everyday payday, my grandmother would add things up and tell him how short we were. She’d go through the bills, figuring how much we could get away with not paying each month. Because we did have a car, we carried paper shopping bags with rags wrapped around the handles when we walked to the grocery store. The rags kept the weight of the food from cutting into our hands when we walked back up the hill. Sometimes Uncle Doug would take my bag and carry it for a while, adding the weight to his own load.

I never heard my uncle complain. He hugged us kids and tickled us, grabbing our legs just under the knee cap and wiggling them back and forth giving us what we called “shinnie, shinnies.” Once he took the four of us children to the Fun House at Playland-at-the-beach. Another time he took us to a roller-skating rink. One time we went with him to watch the Fourth of July fireworks through the fog at Marina Green. He spaded the garden when asked and carried my great aunt to the living room so my grandmother could change her bedding. Then he’d gently carry her back to bed again.

Sometime in 1958, when I was 10, my grandmother began to get phone calls from a bill collector. She’d argue and cry and hang up the phone. She and my mother would go in the kitchen and close the door. We could hear their agitated tones over the sound of the radio. Once I heard my mother say, “That’s the most ridiculous thing I ever heard! Is Doug out of his mind?”

Then I overheard my mother talking to a friend. She said Uncle Doug had signed a contract for Arthur Murray dancing lessons. They wanted the $1,500 right away, and Grandma had finally borrowed the money on the house to make the bill collector go away. My mother said they took advantage of Doug, that he wasn’t bright enough to understand what he had done.

Uncle Doug wasn’t home much after that. Once in a while he’d spend an hour with us kids. He showed us how to rumba and cha cha. I tripped over his brown wing tips trying to waltz. He had rubber footsteps he’d lay out for us to follow on the living room floor. He’d play Frank Sinatra records so we could dance. He bought a black tuxedo with a blue cummerbund. He started to smell like Old Spice and White Shoulders.

One day I found his collection of girlie pictures in the garbage can in the basement. Ants were crawling all over the women’s bare breasts. They got on my fingers and marched around my wrists. I shook them off. I closed the lid.

Not long after that Uncle Doug brought Birdie home to meet us. They were ballroom dancing partners, he said. Birdie showed up with false teeth, a lot of rouge and a powder-blue chiffon dress with a fake fur stole. Uncle Doug’s cummerbund matched the blue in her dress exactly. He put his arm around Birdie when they sat on Grandmother’s burgundy chesterfield. My grandmother flinched when Uncle Doug called Birdie “Mama.”

My mother said Birdie was as Okie as the day was long. Killed her first husband with greasy Southern cooking. My mother said the poor man died of a heart attack while they were in the act. To no one in particular, my mother pointed out that Birdie had six grown kids. My grandmother said Birdie didn’t have the brains God gave a parakeet. Birdie ran a mangle and folded sheets in a commercial laundry. Uncle Doug said he loved her.

They were married at Glide Memorial Methodist Church in 1960. The reception was held at my grandmother’s house. We served a buffet of boiled ham and potato salad in the dining room. Then they sprinkled cornmeal on the basement floor and we kids sat on the wooden steps and watched as Birdie and Doug waltzed and tangoed on the open space near the washing machine. My mother said the marriage would never last. My grandmother said Birdie was old enough to be his mother, that she’d die first and Doug would come back home.

Uncle Doug and Birdie bought a singlewide house trailer in a park in Santa Rosa. For years Uncle Doug took the Greyhound bus to San Francisco to sort mail at the post office at night. He bought Birdie a new washer and dryer. They made payments on a refrigerator-freezer combination from Montgomery Ward.

A few years ago I drove up to tell him my mother had died. He’s retired now. He has a deep scar on his cheek where they took out a cyst. His magnified eyes are dim and he has dandruff and gout. He asked me if he was mentioned in my mother’s will. I said no. He asked if I wanted to hear some Frank Sinatra. I asked if he and Birdie still danced. He said yes.

San Francisco Chronicle, Sunday Punch Dec. 11 1994

Wednesday, February 18, 2015

Why Childhood Memories Matter

|

| Sunnydale housing project, 1941 [Photo: SAN FRANCISCO HISTORY CENTER, SAN FRANCISCO PUBLIC LIBRARY] |

A child ran from the playground at Sunnydale

Projects in the early summer of 1955, beating on doors, breathlessly telling

grownups that I’d fallen from the monkey bars and couldn’t get up. When she

finally found my mother behind one of the uniformly plain front doors, she

explained and my mother came running. Trying to learn how to circle the bar and

come upright like the older kids, I misplaced my hands on the bar and crashed

to the ground, dislocating my kneecap.

I hobbled most of that summer from my bedroom to the

couch. The doctor said my leg had to be immobilized and my mother made sure his

orders were followed. There was no TV in most San Francisco homes. Commercial

TV broadcasts didn’t extend to the West Coast until 1951. Instead, I colored, played

with paper dolls, listened to the radio with my mother, and meditated on the

swirls and flourishes in the burgundy oriental carpet. I went from cast to

elastic bandages, my mother wrapping my knee tightly several times a day.

Eventually I was allowed to walk without crutches, then permitted to go

outside.

That’s how I met her. After walking dutifully for days around

the projects, I went to a building beyond the view of our unit’s windows, and

ran as fast as I could up and down the narrow sidewalks, testing my knee. A

woman came out and asked my name and where I lived. I was only about six and

answered truthfully. I went on running. When I got home, my mother said a nice

lady had stopped by. My knee stiffened and I sat down, waiting for the wrath because I'd been running.

The lady asked, my mother said, if I could come and play with her daughter, who couldn't go

outside because she had polio and couldn't walk. I knew very well how that felt

and agreed to visit.

This fuzzy, black and white, memory comes back to be because

of a recent conversation with my niece. She lives in Orange County and just had

a baby. She’s leaning toward not vaccinating her infant daughter. She asked me

what I thought about that decision. Trying to remain supportive of her parental

prerogatives, I said it was her decision, but the memory of the day I met my playmate

kept coming up.

My mother dressed me in nice school clothes and walked me down

the hill. We were welcomed, I went inside. In the living room was a large metal

cylinder, horizontal sunlight through Venetian blinds striped the gray tube.

Only my friend’s head extended beyond the enclosure, a mirror positioned above

her so she could watch the room. Shocked, the girl’s mother sat me down at a

children’s table. She brought me crayons and a stack of coloring books,

children’s playing cards, board games. She explained her daughter, Eunice,

couldn't walk or sit up, that she had to stay in her iron lung, but she could

watch and she wanted to see me play. I caught her eye in the mirror, sensed

Eunice’s wariness as it slipped into indifference.

Eunice’s mother fluttered about, brought me red Kool-Aid as

I colored. She adjusted me in the child’s chair so I could be seen through the

mirror. I don't recall her speaking. She just made animal sounds that signaled

her mother when she needed attention. The polio vaccine had not yet been

invented.

|

| Members of Rotary International volunteered their time and personal resources to help immunize more than 2 billion children in 122 countries during national immunization campaigns. |

It became available when I was about 10. We all got it, everyone,

including my parents and grandmother. About 1962, people lined up around the

block to receive the vaccine on sugar cubes in the Alvarado Elementary School

auditorium in San Francisco. There were long tables of nurses passing out the

doses to grateful families, every member chewing the sweet protection.

“I respect your decisions about what's best for Adriana and

support you in whatever you decide,” I told my niece, knowing she will make

decisions based on solid information and complete love. I told her I had my sons immunized

because I'm old enough to remember when immunizations were not available,

perhaps with the exception of small pox vaccine, which my mother received in

the 1930s as a girl.

Today, the U.S. Centers of Disease Control says about 30 percent

of measles cases develop one or more complications, including pneumonia, which

is the complication that is most often the cause of death in young children.

Ear infections occur in about 1 in 10 measles cases and permanent loss of

hearing can result. Diarrhea is reported in about eight percent of cases. These

complications are more common among children under five years of age and adults over 20 years old. As

a child, I knew children who were deaf from the effects of measles, the twisted

beige wires of their hearing aids draped across their chests. There was no licensed

measles vaccine in the U.S. until 1963.

“Your father had the most horrendous case of mumps I've ever

seen in my entire life,” I told my niece, hauling up another memory. “His head was literally the size of a

basketball. He was very, very sick for weeks, literally. Joyce, Steve (my

siblings) and I also got mumps. There was no vaccine at the time. Joyce and

Steve were very sick. My case was mild and only put me in bed for a few of

days.”

Chicken Pox: Because there was no vaccine, we all had it, I said. My

own sons had it.

Whooping Cough: There was no vaccine available and fortunately

none of us kids got it

.

“If you've ever heard the sound of whooping cough, you'll

know it. It's a horrifying sound,” I told my niece.

The CDC says: “Whooping cough is very contagious and most

severe for babies. People with whooping cough usually spread the disease by

coughing or sneezing while in close contact with others, who then breathe in

the bacteria that cause the disease. Many babies who get whooping cough are

infected by parents, older siblings, or other caregivers who might not even

know they have the disease. Half the babies who get end up in the hospital,

some die.”

In the fall of 1955, I attended first grade at Sunnydale

School. My mother was president of the PTA. Eunice and I would have been

classmates. She died that winter and her family moved away. My parents bought a

house thanks to the money they saved living in the projects and we moved away

too. But the memory of Eunice, her translucent face and wispy hair spread out

on a pillow, her inquiring eyes reflected from the mirror above her head stay

with me and flood back whenever someone talks about the dangers of vaccinating

children.

I tell you about this conversation with my niece because I survived a time when common

vaccines were not available and hundreds of thousands of children were damaged

or died. I got my children immunized because in my view the risk to their

health and very lives is too great to ignore. I tell you this in memory of

Eunice.

How Anti-Vaxxers Ruined Disneyland For Themselves (And Everyone Else)

Thursday, February 12, 2015

Red-tailed Hawk and a Fractured Valentine

I recently got an email from an old friend of my ex-husband,

who now lives in England. He inquired about John's whereabouts.

I wrote him back with the news.

Dear Dan: Thank you for your kind note about John. I'll pass it on to our sons, Mark, 35 and Mike, 24. I know they'll appreciate your remembrance. They've taken the loss of their father hard and they're still getting over it. They were relatively young to lose their Dad and have been rudderless since, as I've been for the past few years. John was always so big and robust, wherever he went he filled the room. It's still hard to believe a mere virus could diminish him, take him away.

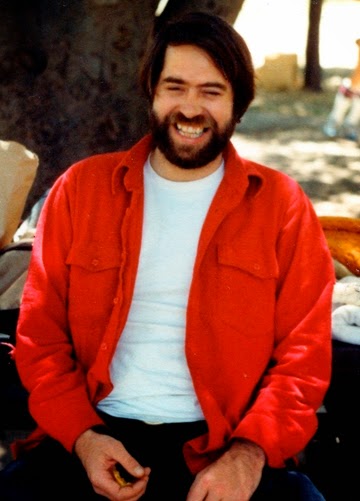

John

and I had a challenging relationship, as you know, and we were not living together when he

died. He died alone by choice and it was a month before his body was discovered. I regret the way he died and miss him very much. He

was my biggest supporter and we all wish we had been there for him. But, in the end, big and gruff, he chased everyone away in his bitterness.

I worked my day job and worked on the novel nights and weekends. It's set in Seattle in 1973, its about what happened after the "Free Love 60s" ended and a new era began -- end of the Vietnam War, Watergate Scandal, Roe vs. Wade that legalized abortion, launching of the war on drugs, the Arab Oil Embargo, etc. The story is about Lizette, an addled street artist who hooks up with the Franklin Street Dogs, a ragtag tavern softball team, it's about the gritty drug scene and the pristine beauty of Orcas Island, its about John and me and the only thing that really matters. But, remember, it's fiction.

I struggled to find an ending for the story, but it eluded me. One night I had a dream, vivid and powerful. John and I were in bed on a sunny morning. We were young. In the dream, he went to take a bath and I went along to keep him company. In the dream every hurt, resentment, tension, grievance between us was resolved and in that moment only comfort, love and acceptance washed between us.

It was as if John came to me in person. It was 2 a.m. and by 6 a.m. the end of the novel was written, the story complete. I had a strong urge to call John, check in, see how he was doing, but put it off. As best the San Francisco Coroner can figure, he died the day I finished the novel. I believe the end of my story was his final gift to me, the gift of feeling his complete, untarnished love, and a gentle, resolved ending to a grating story. Sorry, but I can't go on telling. It makes me cry.

|

| Gerald and Buff Corsi © California Academy of Sciences |

At John's funeral, we had lots of chocolate and roses and friends from John's days in San Francisco's Haight Asbury. When it was over, I went outside and a huge red-tailed hawk swooped low and ruffled my hair then perched on a cornice of the building. You would think this an exaggeration, but I have witnesses.

The hawk was vigilant, as if guarding. It was still there after everyone left and I was alone with this magnificent bird, standing in front of an ornate and historic mausoleum. I hated to leave him there and my brother had to drag me away. We sprinkled some of John's ashes in the Panhandle at Golden Gate Park where he played baseball as a kid. I have kept the rest.

Find Adrift in the Sound here.

Sunday, December 7, 2014

Riding Holiday Waves

We were late getting there, what with L.A. traffic and a not-so

quickie in the truck stop restroom outside Los Banos. The paper towel dispenser was empty. We

took the slow lane, didn’t zip up the highway. Why rush? he said and I

agreed, air dried my hands out the window, trying to picture the people in San Francisco I'd never met.

By the time we landed on his mother’s doorstep, blankets and bags in hand, the family's faces were blurry, blank. I gushed about his mother’s amazing flat, the hardwood floors, the view of the bay, the double glass doors separating the living and dining rooms, skipped over mention of her recenly departed husband, his photo in the place of honor on the mantle. I fluttered, not finding a suitable perch. She said I had beautiful hands, asked me to sit, patted the spot beside her on the sofa.

His brother talked about flying in from the East Coast and how the guy next to him blew snot on the airline blanket and then spread it over his chest. He said the kids get up early, an unapologetic warning, before slouching off to the back bedroom to assess his wife's migraine. We got the living room fold-out without much padding, the inflexible frame now cutting into my spine.

At first light, she began setting the holiday table at a dogged pace. I watched with one eye, riding my attention up over the bunched pillow like a sneaker wave, spying on her as she fondled each dish. Against the foil light of dawn, she moved in sparrow hops from branch to branch around the room.

She flapped a white table cloth, smoothed it with veiny hands, pulled brown napkin rings from a drawer in the battered sideboard, held a gravy boat up to the dim light, set it down. She stood hunched before the windows, wiping her eyes, twisting the wedding band around her bony finger, staring at the first hints of another day.

I ignored the warmth coming from behind, the knucklehead nosing my thigh. Clearly, his mother, lost in reverie, wasn’t blind. I nudged him away, suspected her hearing was pretty good, too. He kept nuzzling. I relented, arched my back, leaked tears, broke like a wave over the rising grief.

From "Hard Holidays" flash fiction collection, because holidays sometimes provide food for thought.

Sunday, September 7, 2014

THEN and NOW

Foghorns lowing in humid voices,

ward off terrible nights, just terrible,

rattling putty-loose panes in your

windows staring blindly at fronds

madly slapping at wind but you sleep

I had been sleeping, my brother

but now I am awake in my child’s

room in the night watching twinkle

lights on boats pitched in the bay’s

foamy throat, horns calling to us

to you lost

in fog wallowing into swells

it is as if your absence opens

the sea’s chasm now, it coughs,

and you still sleep with deep

meaning forever through the end,

carelessly listening to the foghorns

praying their baritone chorus over

a signal light flashing from voice

to voice and I tremble, pull the

coverlet taut across my child’s

breast and when I turn from

the window and from the restless

sea, from loss, from you, the room

fills with dark forest lush with vines

we’ve never seen, frogs croaking

songs we’ve never learned, will

never know, but the anguish we’ll

never lose in the voices of engulfing

darkness, moaning your name

Richard and now that I am alone

I’m ready to confess the awful pain

twisting my conceited heart it

was some trivial dispute that carries

me here, my arms full of ghosts,

of roses, to kneel at your feet

almost ready to see how at each

turning we grew and I chose this way,

this place and and you another but

now this, this converging of ocean

and earth with horns deeply chanting

I can keep going if I listen, if I feel

where I cannot breathe, if I will begin

without you, horns lowing your name

east through the fog, to meet your

rising light standing at water’s edge

at this void beyond voids where

we’ll once again share our child songs

in this empty space where love speaks

in the fog, at this place, Land’s End.

ward off terrible nights, just terrible,

rattling putty-loose panes in your

windows staring blindly at fronds

madly slapping at wind but you sleep

I had been sleeping, my brother

but now I am awake in my child’s

room in the night watching twinkle

lights on boats pitched in the bay’s

foamy throat, horns calling to us

to you lost

in fog wallowing into swells

it is as if your absence opens

the sea’s chasm now, it coughs,

and you still sleep with deep

meaning forever through the end,

carelessly listening to the foghorns

praying their baritone chorus over

a signal light flashing from voice

to voice and I tremble, pull the

coverlet taut across my child’s

breast and when I turn from

the window and from the restless

sea, from loss, from you, the room

fills with dark forest lush with vines

we’ve never seen, frogs croaking

songs we’ve never learned, will

never know, but the anguish we’ll

never lose in the voices of engulfing

darkness, moaning your name

Richard and now that I am alone

I’m ready to confess the awful pain

twisting my conceited heart it

was some trivial dispute that carries

me here, my arms full of ghosts,

of roses, to kneel at your feet

almost ready to see how at each

turning we grew and I chose this way,

this place and and you another but

now this, this converging of ocean

and earth with horns deeply chanting

I can keep going if I listen, if I feel

where I cannot breathe, if I will begin

without you, horns lowing your name

east through the fog, to meet your

rising light standing at water’s edge

at this void beyond voids where

we’ll once again share our child songs

in this empty space where love speaks

in the fog, at this place, Land’s End.

Friday, May 23, 2014

Memorial Day

We were late getting there, what with traffic and a not-so quickie in the truck-stop rest room off I-5 that smelled of toilet bowl freshener. We took the slow lane, didn't zip down the highway. Why rush? he said and caressed my inner thigh. I agreed, but felt fatigued by the time we landed on his mother’s doorstep last night, the faces of his family blurry and blank.

I gushed insincerely about his mother’s amazing flat, the hardwood floors, the view of the bay, the double glass doors separating the living and dining rooms, skipped over mention of her now gone husband, his soldier's photo in the place of honor on the mantle. She'd start with "we" or "he" then stop. "Vietnam," she whispered, following my eye to the photo.

His brother talked about flying in from the East Coast with his family in a nasally voice. He told how the guy next to him blew his nose on the airline blanket and then spread it over his chest. He said the cab from the airport smelled of stale hash and warned us the kids get up early, then slouched off to the back bedroom behind his wispy wife. We got the living room fold-out without much padding, the inflexible frame now cutting into my spine.

At first light, she began setting the holiday table at a dogged pace. I watched through the glass doors with one eye, riding my attention over the bunched pillow like a sneaker wave, to spy her fondling each saucer and candlestick. She flapped a white tablecloth, smoothed it with veiny hands, pulled brown napkin rings from a drawer in the battered sideboard, held up a cobalt glass goblet to the dim light, studied it, put it away, stood hunched before the dining room window, facing east, wiping her eyes, twisting her wedding band around her bony finger, thinking she alone was staring at the first hints of a mimosa sunrise.

I ignored the warmth coming from behind, his knucklehead nosing my thigh. Clearly, his mother, my hostess, was lost in painful reverie. Lost, but she didn't have on blinders. I pushed him away, suspecting her hearing was still pretty good. Relenting with the next nudge, I arched my back and surrendered into her grief.

From Hard Holidays, online flash fiction prompts from writer Meg Pokress, author of best-selling flash fiction collection Bird Envy.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)